When Everything is Fine...Until It Isn't.

A reminder that, to quote a former professor, "all death is tragic."

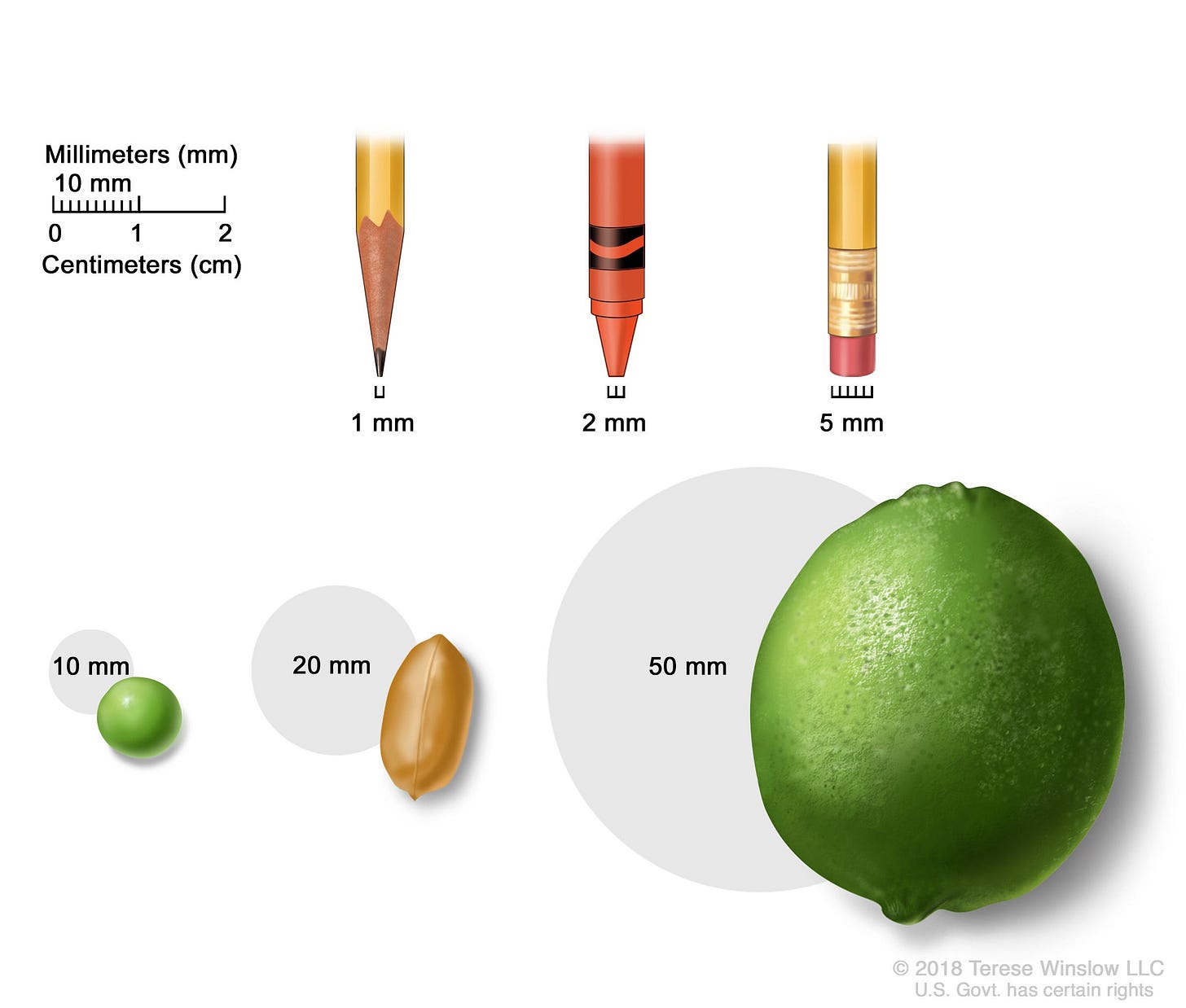

Three millimeters. Take a penny and stack it on a nickel. Together, that’s 3 mm thick. Not much, right?

Five millimeters. It’s about the size of the pink eraser that sits atop the golden painted pencils on sale at local stores for back to school. Again, not that big.

Ten millimeters. Fresh spring peas are so good. I don’t have as much love for the frozen varieties my parents would overcook or the vegetable medleys of peas and carrots dumped on my plate at our college dining hall, but there’s nothing better than a fresh one. Anyhow, a single pea is about 10 mm.

There are about 20 major arteries in the human body, most of which are between three and five millimeters in diameter. Your aorta, the main highway to the heart, can be up to 10 mm. When the heart pumps, it pulls oxygenated blood into itself through the aorta, then pushes it back out through the body.

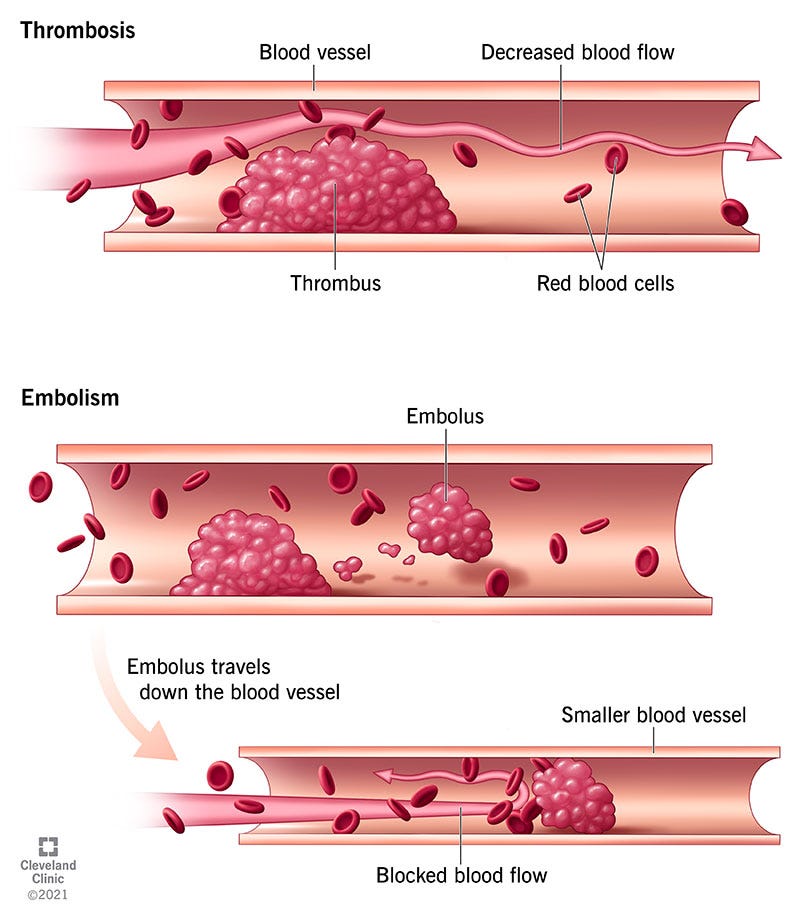

Sometimes, arteries constrict. Smoking, dietary choices and bad genetics, amongst other things, can cause those arteries to narrow as plaques — a mish-mash of calcium, cholesterol, lipids and other unfiltered material — build up on their walls and hardens. It’s like pinching or kinking a garden hose, making the heart work harder to push blood through the tiny three- to five-millimeter pathway so that fresh blood and fresh oxygen can feed cells within the body. Everything is fine…until it isn’t.

We installed a pool this last fall and finally turned on the filter for the first time in the spring. The filter was running fine until it wasn’t. We noticed that there was a weak stream from the jets returning water to the pool from the filter and, eventually, we’d lose pressure altogether. When the pressure builds up too high and the gauge goes past about 20 PSI, you’re supposed to run a tube away from the filter and backwash it until the water runs clean; we didn’t know that. It gets all of the accumulated crap out of the filter from daily use or vacuuming. Once it runs clean, you flip it back to filter and everything is fine until it isn’t, again.

The human body has no such setting. In fact, it works a lot like my neighbors’ pool filter. They went to bed one night with a working filter and the next morning they had a dead pump. Something had caused a leak, leading to the pump to run dry and burn out. There was no warning, no symptomatic alert…nothing. It was fine until it wasn’t.

Plaques can break away from the wall of an artery for any number of reasons, all beyond my comprehension as someone with two journalism degrees1. I imagine microscopic flakes come off regularly and filter through the body with little affect. But, when a big enough plaque dislodges, it’s called an embolism. More specifically, a blood clot. Big clots float around until they can’t anymore, blocking the flow of oxygenated blood to the heart and backing up the plumbing along the way.

Let’s forget about everything building up in its wake, because the bigger problem is that the pump is about to burn out.

Call it a heart attack or cardiac arrest. Maybe if you watched er during the 1990s, House during the aughts2 or Chicago Med now, you learned the phrase myocardial infarction. Whatever term you want to use, the point is that a person has mere minutes from the moment the heart stops pumping to get treatment.

Sometimes, there are signs. Nausea, chest and upper body pain, dizziness and lightheadedness precede a cardiac event. Other times everything is fine until it isn’t.

Sometimes, you can get a dose of thrombolytic medicine to bust up the clot. If the ambulance delivers you to the hospital in time, there might be a stent installed, an angioplasty balloon inserted or an arterial bypass to jump the blocked area. My late friend Marty had at least four bypasses after his heart attack. One of my favorite profs from college had seven after sustaining his second, which he had while making copies for our mid-term one winter morning.

Other times, there is no notice. One minute you’re mowing the lawn and the next minute, you’re not, as was the case of the husband of my former boss. Everything was fine until…it wasn’t.

And then the text message pops up on your screen.

“I’m not sure if this news has made it to you, but so-and-so passed away. I’m hearing it was a heart attack. I don’t have many details but I’ve heard now from more than one person.”

When you’re family or a close friend, you’re more likely to get a phone call. If you’re like me, and it’s a colleague that you work with but with a wide separation between your roles, you get a text message.

A colleague that always asked what restaurant you’re reviewing next, or whom you’re expecting to rag on you about something, but just wants to make conversation because he was just a good dude.

A colleague who, on your sixth day of work with the company, you followed around because of an incident that occurred in the scope of his work that was public, and you needed his help to respond to local media asking questions.

A colleague who spent more time than he needed to explaining every bit of information he knew so you could sift through the details and do your job.

A colleague who was a giant — physically and metaphorically — and simply one of the nicest and most gregarious people you’ve had a chance to work with.

And then word sneaks out and you start getting the phone calls and texts.

Or, maybe you become the caller and texter that reaches out to others. “Has anyone called you yet?” you ask your manager before gently breaking the news. You send text messages to your peers that knew him tangentially as a voice on a conference call.

The grief comes later, but it’s the shock of the news that hits you in the face because you realize that everything is fine with you too, and there’s a chance it might not be eventually.

My friend

and I sat together in JMC 106 (Newswriting and Reporting)3 at St. Bonaventure University when Dr. Steve Koski delivered a lesson that has been both a punchline and important reminder to us both: All death is tragic. Now, Dr. Koski meant that in our writing we should stick to the facts. Whether a heart attack or murder, death is always tragic. There are no degrees of tragic. Life is binary: you are alive or you’re not.The fact is that we will all die and there isn’t much we can do to determine our fate to that end, so it’s the time we have that counts. I wrote briefly about the death of a friar from St. Bonaventure University last week — another giant life — after a short illness. We all knew Fr. Dan would one day die and leave a hole in the world larger than the campus he inhabited; a prophecy fulfilled through a beautiful service that was videostreamed to satisfy an overflow crowd at the college and alumni watching at home.

I knew that my mother would one day die, but was not expecting the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and the long summer of watching her waste away. The morning I got The Call to come home set me up for a four- or five-day haze of numbness. I had months to prepare and ready myself. To say goodbye. To begin grieving before she died.

I think my colleague and his family were cognizant that life is short and that we all eventually die. His family, like millions of others before them, were robbed of their goodbye and their preparation.

My former neighbor4 and I have chatted about this in short doses. The topic, usually brought forth when multiple cocktails have been consumed, revolves around the same question: Is it worse to lose someone immediately or to watch them slowly die?

We never come up with an answer.

What do have are the words of Dr. Koski: All death is tragic. And, whether it’s an accident, cancer or otherwise, you deal with the same truth that everything was fine until it wasn’t.

Final thoughts on finality…

If death shall be an endless sleep

where all pressures, dreams shall cease,

one would never have a need to weep

lying in eternal peace.

If death should bring one to the place

where spirit world doth reside,

let us welcome then that saving grace

with these spirits then abide.

In death I see no cause for fear

when it comes as sweet relief,

instead, I see a cause for cheer

freed from trials and freed from grief.

— Joseph Anderson, Ode to Death

Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning. Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop a line at jaredpaventi@substack.com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook, Twitter/X, LinkedIn and Bluesky. I’m on Threads and Instagram at @jaredpaventi.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. For additional mental health resources, visit our list.

What idiot gets two journalism degrees? It’s a long story for another time.

Ugh. That fucking show.

Now JMC 201 and 202.

Her father died rather suddenly when she was a teenager.

Well done Jared. Hits very close to home (my Dad at 34) and an officiating colleague just last week. Well done. Pax et Bonum

The other lesson from that lesson: Never write “died suddenly.” All death is sudden. You’re alive and then you’re not. What you, the journalist, mean there is “died unexpectedly” or something like that.

Wonderful piece and I’m sorry for your loss.