Maraṇasati: Death is All Around Us

How to achieve mindfulness of death through meditation plus an interview with author Margaret Meloni

Back in the Before Times1, my co-worker Toni and I would regularly go into her office, close the door, unplug her phone and do a guided meditation together2. It was usually something we did during our nonprofit’s event season to center our thoughts amid the chaos of venue changes, left-field requests and administrative demands.

We’d dial up a 10- or 15- minute guided meditation for mindfulness on Spotify and try to achieve some balance in a period of time where everything was seemingly out of whack.

I don’t do guided meditations frequently, though I should. It’s something I save for periods when my brain is moving at 100 mph and won’t slow down. A 15-minute guided meditation on those mornings helps me bring some order to things. I acknowledge the thoughts, process them as things that can be solved immediately3, can wait until later4, are too big to solve on my own5 or are just bigger than me6.

Garrett Kemps, he of the most excellent Substack newsletter Healings and recent subject of a Q&A here, sent along an article on the Buddhist practice of death contemplation, or maraṇasati. My knowledge of Buddhism (and eastern religions, for that matter) is thin so I’m going to let someone who knows more explain it:

The Sattipatana Sutta, where the Buddha laid out the essentials of mindfulness practice, includes a cemetery contemplation. At the time of the Buddha the yogis would go to actual cemeteries and sometimes live there for extended periods of time. Often the dead bodies were not buried or burned but just discarded, left in cemeteries, out of compassion for the animal kingdom, for vultures and other animals to eat. So yogis would observe the human body in various states of decomposition and work with what that brought up in themselves. The whole point for these yogis was to see that whoever this body belonged to had been subjected to the same law that they were subject to.

Detour…

A very quick primer on Buddhism7:

Buddhism was founded in about 5th century B.C. in Southern Asia. Buddhists don’t believe in one god, but figures that can guide or deter them from achieving enlightenment. Buddhists believe in reincarnation, and that one exists in a cycle of suffering and rebirth with the goal of achieving enlightenment — a place where the binds of suffering are broken.

Siddhartha Gautama, a Nepali prince of that era, is regarded as the first person to achieve enlightenment and ascended to the title of The Buddha. He taught about the four noble truths: Dukkha, or that everyone suffers in some way; samudaya, origin of the suffering; tanhā, desire is the root of all suffering; and nirodha, the cessation of suffering.

There are three branches, or schools, of Buddhism. Mahāyana, popular in China, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, believes that those who have achieved enlightenment — bodhisattvas — are individuals who have returned to teach and free others. Theravāda stresses that the individual gains enlightenment on their own. It’s most popular in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. Vajrayana is a derivation of the Mahayana school, rooted in the Indian subcontinent, and offers a faster path to enlightenment.

Death is all around us…

What we’re talking about is mindfulness about death and from every possible angle, from mere contemplation or the fact that death could come at any moment to what happens to the body when our soul leaves it and the container is all that is left of us.

Mindfulness of death is not intended to be a morbid practice or some sort of zen-goth crossover. Remaining mindful that death could strike at any moment helps the person deepen their appreciation for this life they have been granted and to impress upon them the notion of doing good and seeking fulfillment. From that, one develops a greater sense of self and is able to find good in others.

The natural byproduct of that is a reduction in the fear and anxiety of death because you have made peace with the fact that it will happen.

It’s not giving up or submitting to death. It’s accepting the random, unpredictable nature of death so that you can embrace and appreciate life.

Now, this isn’t your average meditation about mindfulness. We’re talking death here, so you need to do an honest level-set as to your condition in the moment. It starts with the acceptance of death. You must accept the fact that you and others will die, and that every second that passes is one less second in your life. After all, the time you can devote to achieving mindfulness is decreasing.

You also have to assess how you’ve dealt with death and grief previously. Achieving mindfulness in the contemplation of death will present emotional triggers, so say the experts, so if you’re not good at handling feelings of grief, this may not go smoothly at the outset.

The next step is to accept that death is all around us. Again, not in that earthquake kills 2,000 people sort of way, but something more real to you.

It’s autumn and leaves are falling from the trees. Leaves that were once green and feeding the maples and oaks in your yard now crumple beneath your feet.

The flowers I brought home for my wife a couple of Sundays ago have begun to shed their petals, their life long ago ended for bits of aesthetic and emotional pleasure.

A deer on the side of the road, struck by a car and left to rot.

By accepting that death is naturally occurring and always around us, we can look inward and achieve contemplation of our own place.

Q&A with The Death Dhamma

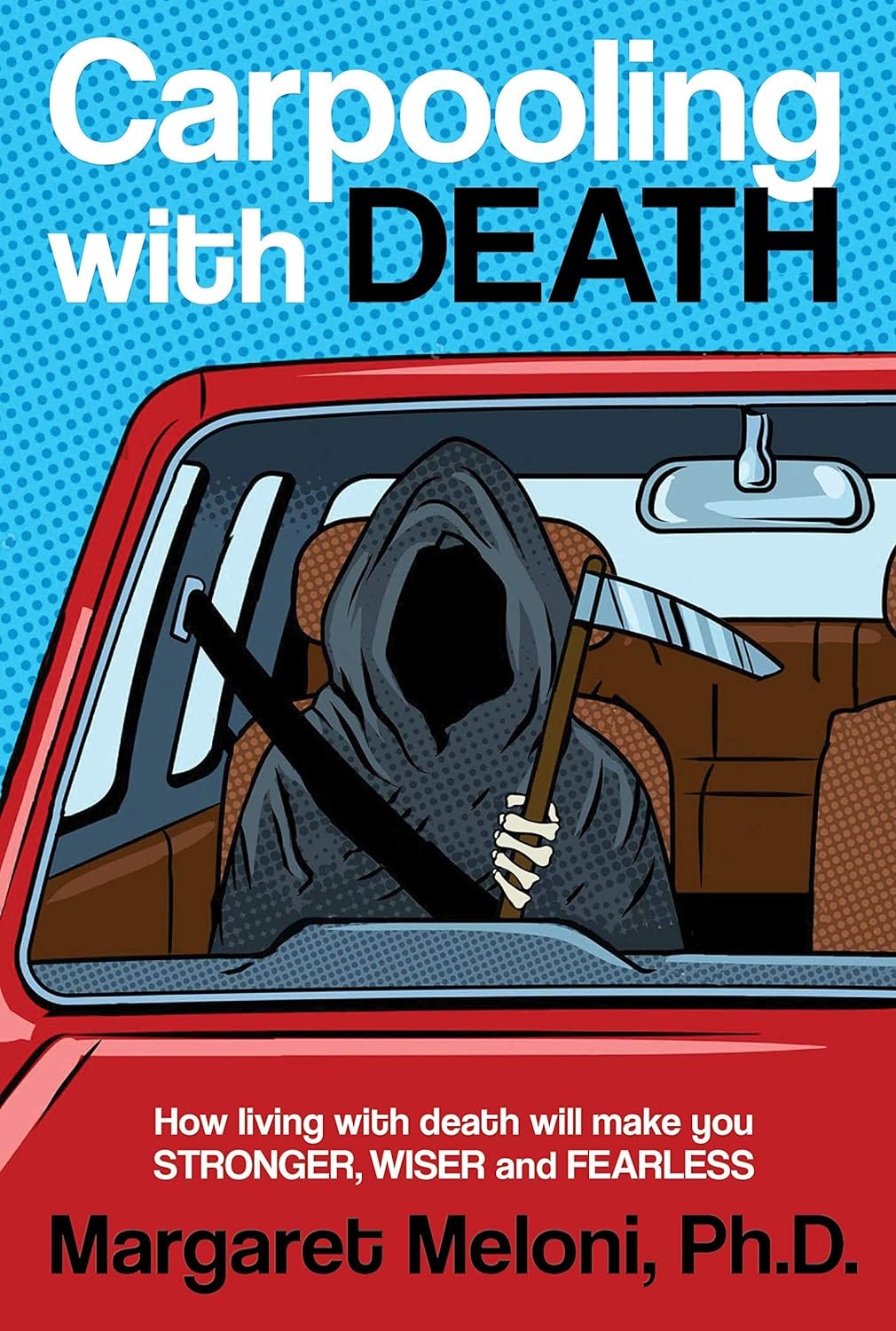

Margaret Meloni is a practicing Buddhist, she is a speaker, teacher8, podcast host and author of two books — Carpooling with Death and Sitting with Death. The former focuses on how to accept death into your life so that you can cope with their passing, and find strength and inner peace. The latter is about bereavement, or accepting death when it has already taken someone from you. Her website is a jumping off point for her work. She is known in these circles as The Death Dhamma.

Margaret was kind enough to answer a few questions about meditating for death and how inviting death into her life got her through her most trying times. Her answers have been edited (lightly) for brevity.

Speaking generally, what does the Buddha teach his followers about death, dying and grieving?

Once we are born, we are going to die. And we will be in a cycle of birth and rebirth until we find a way to release our suffering. This passage from the Udana9 concisely states our reality:

Those who have come to be,

those who will be:

All

will go,

leaving the body behind.

The skillful person,

realizing the loss of all,

should live the holy life ardently.10

That last phrase, should live the holy life ardently, means to go all in on your practice. At the time of the Buddha, of course it was not called Buddhism.

But he meant to really understand the root of your suffering and to work to gain release from that suffering. To be born as a human gives us the opportunity to engage in the practice and to live in a way that will help us gain freedom.

We gain an understanding of that suffering from The Four Noble Truths. It is fair to say that the Four Noble Truths are accepted across the various Buddhist Traditions.

The Four Noble Truths included below, along with my own thoughts on grief.

There is stress and suffering or dukkha. Another way to think of this is that in life, we have much dissatisfaction. In grief: I am experiencing sadness and suffering. This is dissatisfaction. I don’t want to feel this way, but here I am. This is what I feel.

We experience this dissatisfaction because we become attached to either wanting good things to stay the same or for difficult things to stop being difficult. (Ed. note: A combination of samudaya, the origin, and tanhā, that desire creates the suffering.) In grief: I feel sad. I miss my partner. I did not want him to suffer, but I also did not want him to die. And now, I am alone. I don’t want to do this. He would be the one to help me feel better. But he is gone. I wish that were not true. I wish that our lives together could have continued.

There is a way out of this dissatisfaction. In grief: This is hard, but it will not always be this way. It is not going to change overnight, but it will change. And I have the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha. I have what I need to walk through this suffering.

The way out of this dissatisfaction (Ed. note: The nirodha, or cessation of suffering.) is to live your life per the Noble Eightfold Path. In grief: Right view is my first step on the path. It is right view that allows me to see my suffering for what it is. It helps me to understand that I had an attachment to my loved one. Right view also reminds me that to be sad or to miss my loved one does not make me a bad Buddhist. Now, I can begin to use right intention to help me treat myself with loving-kindness and compassion.

It is normal for us to experience grief, either for ourselves as we age and change, or as the people we love age and change, and of course anytime another being who we love dies. That could be a human or a pet. I mention pets because many of us live in a society where our pets have like close friends and family members.

Grief is a natural process that accompanies death. How does the Buddha guide us through this process and what is the end goal of it – acceptance, life without the other person, etc.?

We want to come to a place of peaceful acceptance, to develop equanimity.

Equanimity means that we accept death. It is one of the many events that make up our lives. In one moment, you might be with a friend who has just lost her husband and in the next moment, you receive a text that your other friend is newly engaged. On the same day, you might learn that a former co-worker has died and then you receive a text about someone else’s new baby.

All of these moments are important and are meant to be experienced with equanimity. This does not mean without feeling. It means to direct your energy and emotions in the best possible way. Be happy for your newly engaged friend. Don’t be manic about it. Be sad at the loss of your co-worker.

The Buddha taught us suffering and the release from suffering, within that context, to become comfortable with death and grief is to become closer to being free of clinging and craving and attachment. It is not wrong that we are sad, it it not wrong to love other beings, we also need to learn that we are all subject to impermanence. To accept that the time we have will not go on forever. This is not meant to bend us toward nihilism, rather go all-in and live. Instead of avoiding experiences in life, learn the most you can from those experiences. Instead of avoiding relationships with others, be fully in those relationships, without attachment. Learn from the present moment because it will be gone. Don’t think, “Why bother? This will not last.” Do think: “This opportunity will not be here again. Let me really be in this moment and let it be my teacher.” Be aware of death. And let it encourage you to live.

I’ve read some about maraṇasati, or achieving mindfulness through the awareness and contemplation of death. Why is it important, in Buddhism, to achieve mindfulness in death?

In Aṅguttara Nikāya 6.19, the Buddha says to his monks,

“Mindfulness of death, when developed and pursued, is of great fruit and great benefit. It gains a footing in the Deathless, has the Deathless as its final end. Therefore, you should develop mindfulness of death.”

In the above quote the reference to the Deathless means Nirvana. To be free from the cycle of death and rebirth. The ability to contemplate death, to let go of your fear, and to let go of your attachment to life helps you to reduce your clinging, and aversion. And a comfort with death will help you have a more peaceful death. A peaceful death is a contributing factor to a more positive rebirth. If you are going to be reborn, to return as a human is the best outcome, It is here in the human realm that we have the ability to practice Buddhism.

Learn from the present moment because it will be gone. Don’t think, “Why bother? This will not last.” Do think: “This opportunity will not be here again. Let me really be in this moment and let it be my teacher.” Be aware of death. And let it encourage you to live.

I have used guided meditations for mindfulness and sleep in the past, but never for death. We’re not talking about your average 10- or 15-minute meditation in this case, are we?

There are quite a few ways that you can approach mindfulness of death meditations. Some are longer than others. I do not know that the value comes from the duration, rather it comes from the concentration and the ability to work on the difficult emotions that surface.

You can say that MOST of us need to revisit this type of meditation over and over again to become comfortable with death. And that can certainly result in lots of time spent. Initially, for MOST of us it is a good idea to start with something shorter and less emotionally intense and then sit for longer periods and dwell on the more challenging aspects of death.

Each Buddhist tradition has helpful mantras, chants and meditations. When I first approached this I started with reminding myself throughout the day, “This could be my last day.” That was a very helpful beginning.

If you were coaching someone through a meditation on death for the first time, what would you have them do?

In the spirit of honesty, I rarely lead others in meditation. In terms of overall becoming death ready, I often recommend these steps:

Training Level One: Impermanence

If you follow the lesson on impermanence to its natural conclusion, it is not just your thoughts and emotions that are rising and falling. Everything is rising and falling. Every one of us rises and ultimately falls. It is important to remember that everyone is going to experience death.

Recognize that everything will change. We are all subject to old age, sickness, and death. Old age is a gift. The more you can become comfortable with the knowledge that you cannot keep everything and everyone you love, and that you cannot avoid the things you do not enjoy, the closer you are to the end of suffering.

It is not just good times and bad times that will pass; we will too. It is useful to work with the phrases, “We too shall pass.” “I too shall pass.” “Mom and Dad too shall pass.” “[Beloved friend/partner] too shall pass.”

It is not about whether you and your loved ones will die. It is about when you and your loved ones will die.Training Level Two: Keep death in mind

You would do well to spend time considering death and thinking that today could be your last day. That this could be the last day of someone you love. The purpose of this practice is not to dwell in a place of morbidity but to appreciate the preciousness of the life you have been given. To be born as a human being is a gift. In this lifetime, you can practice the Dharma. After you die, you might lose this opportunity.

You can save yourself a tremendous amount of pain with some preparation. You do not have to walk around obsessed with death; just hold the possibility of death in your thoughts.

Think about death throughout your day. Use death as a meditation device. Consider the phrase, “Today could be my last day.” Death is just one of many experiences that make up a life. It is neither good nor bad. It just is.

One way you can make it easier is to accept death as an integral part of life. A way to accept death into your life is to allow yourself to think about it. Don’t turn off thoughts about losing others. Don’t turn away from people who have experienced loss. Be part of that experience.

Ignoring people who are sick does not make them well. Refusing to acknowledge death does not make you or anyone else immortal. The more you wish to avoid suffering, the harder it will be. And the more you crave or want for the people you love never to have to leave you, the more difficult it will be when they do.Training Level Three: Practice the Five Contemplations

The Five Contemplations combine a healthy recognition of impermanence with death awareness. See? Like a good training plan, level three is drawing from the foundation you built for yourself in levels one and two. Most of the Buddhist monks and nuns that I know chant these contemplations every day. Place these contemplations where you will see them and remember to recite them. Please pay attention to these words and the impact they have on you. Use them in your meditation practice.

“There are these five facts that one should reflect on often, whether one is a woman or a man, lay or ordained. Which five?

“‘I am subject to aging, have not gone beyond aging.’ This is the first fact that one should reflect on often, whether one is a woman or a man, lay or ordained.

“‘I am subject to illness, have not gone beyond illness.’. . .

“‘I am subject to death, have not gone beyond death.’. . .

“‘I will grow different, separate from all that is dear and appealing to me.’. . .

“‘I am the owner of my actions, heir to my actions, born of my actions, related through my actions, and have my actions as my arbitrator. Whatever I do, for good or for evil, to that will I fall heir.’” (AN 5.57)

Training Level Four: Meditate on death

Meditating on your death and the death of your loved ones is beneficial. It is also challenging. That is why this is level four of your training plan.

When my father told me that his lung cancer was terminal, I meditated on his death. Not so much on the actual moment of his death, but on the fact that he would die, I meditated on him being dead and how I would feel about it. I shed many tears, but it helped me to wrap my head around the fact that he was dying. I used the same approach when my husband was dying.

Long before you have a loved one with a terminal diagnosis, you can develop a solid maraṇasati or mindfulness of death practice. In the Satipatthana Sutta (MN: 10), instructions are given on how to contemplate the body as a body that has been disposed of in the charnel grounds. And remember that just as that body has met various stages of decay, so too will your body. Your body is no different from that body in the charnel ground.

The Kāyagatāsati Sutta (MN: 119) teaches mindfulness of the body and again refers to charnel ground contemplation to remind us of the impermanence and dissolution we all face.

The Maraṇasati Sutta emphasizes the importance of the mindfulness of death. Not just because it makes it easier for us to deal with death, but because it reminds us to be more dedicated to our spiritual practice.

These are not hidden teachings, they are commonly taught in many parts of the world, yet they could be new to you. And if that is the case, remember to seek out a qualified teacher and practice with your local Buddhist community.

Know that each time you encounter death, your experience will be a bit different. And if you approach each death from a place of openness, you will improve your practice. You will become stronger.

I imagine that once you open the door to this contemplation it could lead to new thoughts that require examination. Where have you seen this journey take others or yourself?

How did this contemplation help you in your own experiences with death? What did you learn about yourself from your own practice?

This ability to openly and honestly notice grief in my life, and name it and sit with it has helped me become more compassionate toward others. It has helped me understand that grief is ever-present. We do not do a terrific job recognizing it - but it its part of our daily lives. And with the idea that everyone is grieving something, I also understood that we all grieve in our own way. This helped me to be less judgmental toward others. To understand, that it does not matter gif I think you suffered a loss, if you suffered a loss you will grieve. You will grieve in your way and on your timeline. My job is to give you loving — kindness and compassion — and to do the best I can to support you in your grief journey.

Margaret’s podcast, The Death Dhamma, is available from the major podcast services.

When you’re ready…

Nearly every source I’ve read says to take it slowly at first and not to overdo it. Find your balance and peace, concentrate on your breath, and sit with a question or thought:

Here’s a possible scenario: You take up a thought, let’s say, “Everyone has to die.” Then you have license to bring that thought inside, to reflect on it, to contemplate it. This is where the practice can become very creative. Each person can do it in his or her own unique way. You can, in a sense, have a conversation with yourself: you can speculate, you can draw on the richness of your own life experience, you can call up specific images, objects, people. You can visualize yourself dying, or people you know who are already dead; you might visualize your family plot at the cemetery or perhaps your own skeleton. The degree of samadhi, the degree of calm and concentration that you bring to your contemplation has a great deal to do with the quality of it and the fruit you receive from it. If you have a strong samadhi practice already, you will become very rich. You can question, reflect, and play with it.

— Tricycle

I am more apt to meditate with a guide, so I have done this one a couple of times. I am still working with it, so no results to report, but I think it might be a good starter meditation if you’re so inclined.

Share your story

I want Griever’s Digest to grow into a place where people can read about someone’s grief journey and find parallels in their own lives. I’m slowly building this bench of stories and want you to be a contributor. You help with the voice and I’ll help with the words. Email me at jaredpaventi at gmail dot com.

Final thoughts on finality…

“Their grief is in proportion to their affection they know their loss to be irreparable.”

— Jane Austen’s tombstone at Winchester Cathedral

Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop us a line if you have interested in either space at jaredpaventi at gmail dot com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook, Twitter/X and Bluesky. I’m on Threads and Mastadon at @jaredpaventi, but I don’t check either regularly. You could message me on Instagram or LinkedIn, but I’m highly unlikely to respond.

Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others. The ego boost of inflated readership stats is all we need to get by.

Pre-Covid, so before March 11, 2020.

I know what you were thinking, pervert.

Example: I need to shift my weight because my back hurts.

Example: I need to take chicken out of the freezer for dinner.

Example: What are we going to do about my oldest and her cell phone usage?

Example: Shutting down the government is going to have massive ramifications that transcend politics and cause real pain for people at a time when Congress should be trying to prove it can function.

I’m doing a disservice here with the brevity of this summary, but I need to set a baseline of knowledge.

Or dhamma, a teacher of Buddhism.

The Udana is part of the Pali canon, the scriptures related to the Theravada branch.

Ud 5.2