Laura Lewis: The Girl Who Tackled Cancer and the Ropes Course (ft. Kate Torok Lewis)

"I have missed her advice over the last three decades, and sometimes get really angry that she was taken from me."

Laura Ann Lewis couldn't wait to get her driver's license. As soon as she picked it up, she planned to get a set of license plates for handicapped people. That way, when she drove her friends to the malls, they would be guaranteed the best parking spaces.

She never drove the elegant, gray Saab she always hoped she'd have someday. Laura of Liverpool died Friday and was buried today, just shy of her 16th birthday.1

Church was my third space as a child, which is ironic given how intensely skeptical I’ve become about religious dogma. I had a mostly stable home for the 1980s, attended a stereotypically suburban elementary school that was whiter than a jar of Duke’s, and spent my weekends at St. Joseph’s the Worker Roman Catholic Church2 in the village of Liverpool.

Saturday mornings were for basketball. I played in the elementary and middle school leagues. When I got to high school, I would help to run the middle school games. Sundays were for mass, except when they weren’t. We more often than not attended the Saturday evening vigil, a bit of church modernization that became a permanent fixture in the 1980s.

While she wasn't able to have the normal teen-age life she longed for since her diagnosis of cancer 18 months ago, Laura left her friends with memories, laughs and some wisdom.

Several of her closest friends gathered at the calling hours held for her Sunday. While hundreds of people lined up to walk past Laura's casket, eight friends sat in a small room off the lobby at the Maurer Funeral Home in Moyers Corners and talked about the girl they miss.

My parents liked to leave church as quickly as possible so we didn’t get trapped in conversations, or could head to whatever called us next — the roast in the oven, grocery store, breakfast, etc.

As such, we regularly sat in the last row of pews for mass. Sometimes, after communion, we would skip returning to our pew and stand at the back of church to jump ship before the recessional made its way to the back.

Rebecca Rosbrook, Laura's friend and cousin, was at her bedside with her family and friends when she died.

“I was the last person to talk to her before she died,” said Rosbrook, 16, a sophomore at Skaneateles High School. “She couldn't see and she couldn't talk anymore, but I leaned over and told her I loved her. I don't even know if she knew it was me. And then it felt like she left, but she took a huge part of me with her. There's still an empty space.”Laura kept her friends going during the bad times. She didn't hesitate to love them or to continue their lives together, even though hers had become a routine of doctors' appointments, hospital stays and treatment. She couldn't go to Liverpool High School, where she was a sophomore.

It became our spot, in the way that families had their preferred seats in the church. The Buttiglieris always sat about five rows from the front. The Cavallaros sat all the way to the right, about one-third of the way down. The Schewes always stood at the back of church. The Lindemans always sat to the far left of the altar. And, the Lewises generally sat towards the opposite end of the row in front of us.

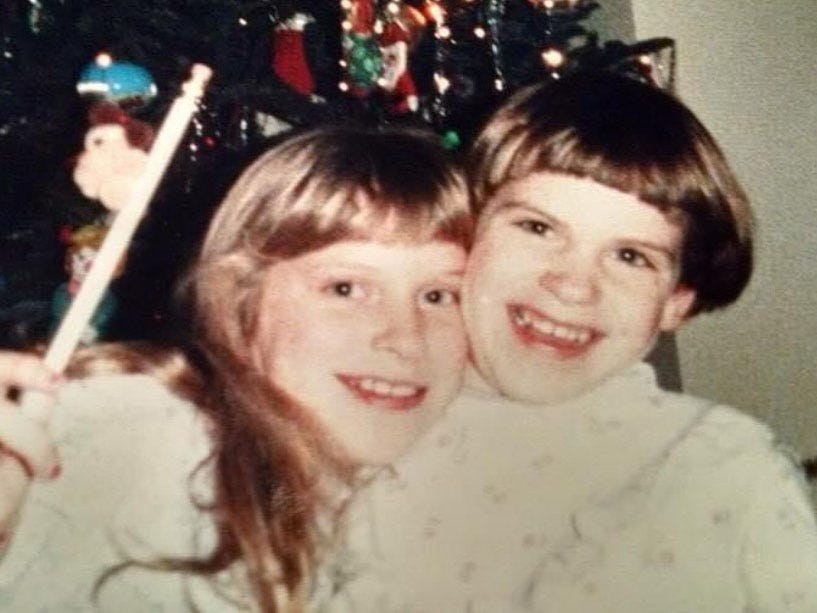

Liverpool, or at least my corner of it, was pretty cookie cutter: a lot of white people and a lot of families of four. So, whenever you saw a family with more, they stuck out. There were six Lewises — parents Ann and Bob, and daughter Laura, Kate, Meghan and Kelly — which made them rather conspicuous.

Jodi Thompson remembers when Laura told her she had cancer.

“My mother and I went over to her house, and we were up in Laura's room with her mother,” she said. “Laura couldn't tell us, so her mother did. And we all just cried.”Laura went out of her way to keep her close-knit friends together. Facing death gave her a clarity of thinking unusual for a 15-year-old.

“She was very wise,” Piper said. “I feel like I learned more from her in this past year than anything else that's ever happened to me. She thought about life a lot.”

The Lewis kids went to different elementary schools than me, so I didn’t know them well. Laura was two years older than me and Kate was two years younger. We were all altar servers, so I knew of them primarily by their names on the mass schedule.

At one point, Laura’s name moved from the list of altar servers to the one read during the prayer of the faithful, requesting extra intentions for the sick. She was the only child on a list of older parishioners and retired clergy and nuns.

One Sunday, Fr. Charlie Major — the parish priest — struggled to share the news of Laura’s passing with the congregation. Fr. Charlie was this towering white-haired gregarious priest. He looked far more intimidating than he was, but had a rather even emotional presence. On the night my mother died, he came to our house, offered condolences, led some prayers and did a final anointing, before leaving. Empathetic, but doing his job.

Charlie was very emotional in sharing the news of Laura’s passing. I don’t remember what he said, but that it was the first time I ever saw him on the brink of crying.

Three weeks before her first chemotherapy treatment, Laura teased her friends about what lay ahead. She'd yank on a handful of her hair and say, “‘This is real for only three more weeks,’” said Julie Hathaway, 15, another classmate. Then they'd all collapse into giggles.

She hated the scratchiness and the fakery of wearing a wig, preferring the floppy white hat she was buried in.“She hated to take that hat off,” said Jeff Piper, 15, a friend and classmate. “She hated even to let her mother wash it.”

A few weeks ago, we talked about dying before your time, or how a person’s life could end before they really had a chance to live. Shane Colligan fit the bill, having died at 23 after two heart transplants, the result of being born with a three-chambered heart. So does Laura Lewis.

Parents aren’t supposed to bury their children. Sisters aren’t supposed to mourn their oldest sibling until they are well into their golden years. But, in 1991, my friend Kate Lewis Torok stood by as her sister, three years her senior, passed away.

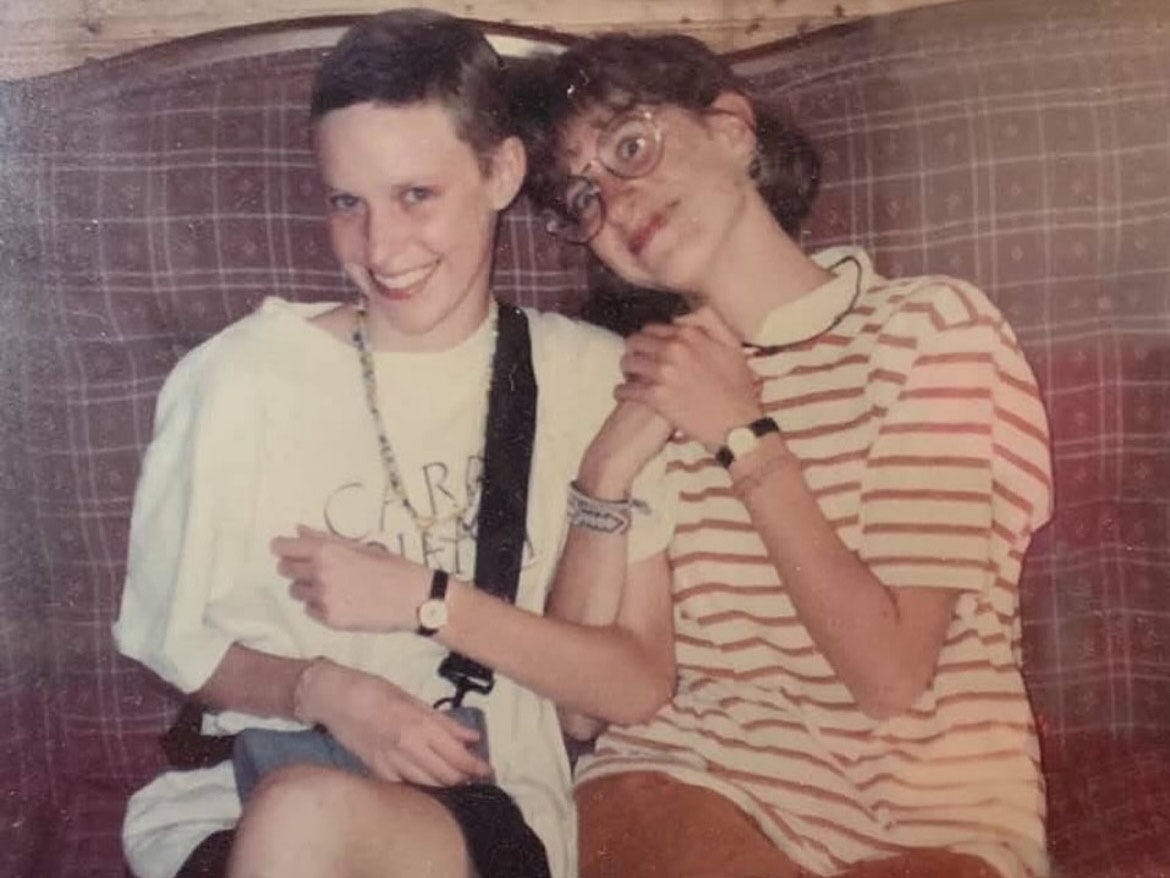

Kate and I both attended St. Bonaventure University and we each work in public relations. Coincidentally, she was classmates with Shane Colligan, a common thread that seems to unite many alumni of my vintage. She was kind enough to share and how Laura still shapes her life to this day.

Laura’s Way

by Kate Lewis Torok

Laura was a spitfire. The quintessential big sister. The kind who would lovingly bully but also defend you. She was kind, adventurous, bold, caring, a wonderful and reliable friend, athletic, funny, charming, and genuine. She was, and still is, my hero.

I remember the day she fell on the soccer field in pain, and the look on my mom’s face. A nurse, she knew something was definitely not right. It was a different fall. The timeline of events from that point on is a bit fuzzy — but there were x-rays, biopsies, consults, and a diagnosis. My grandmother was watching us when my parents were at an oncology appointment with Laura. I heard the car pull into the driveway and perched myself atop the stairs; I wanted to hear the conversation when they came in the door, but couldn’t bear to watch it. “She has cancer,” I heard. And at that moment, one that will remain crystal clear in my mind forever, things changed. And my 11-year-old brain thought she would die. Imminently.

Overnight, we became two old souls. Still sisters, but better friends. She was faced with challenges and in some cases, decisions, that absolutely no one under the age of adult should ever have to face. She became a model human to me — one who showed me how to deal with adversity, how to show bravery, what to do when the cards you are dealt aren’t quite what you imagined, and how to hold on to every ounce of the life you’ve been given and continue to show up for yourself and for others. I have yet to master any of those things, but I channel her every time I am in a situation where one of those heroic actions would be appropriate and I try to make her proud. And when I reflect on my actions, I always think, “My goodness, how did she do it at just 14 years old?”

We definitely still had our spats, as sisters would. But there was a new gentleness. A common understanding. A kinship. She became my forever best friend. There were four of us. She and I were No. 1 and No. 2. We became a pair.

Throughout her illness, there were ups and downs. There was also a brief period of remission. But there are a few memories that stand out. The first was when she learned to walk with her prosthetic without the help of a walker. She lost her leg during her first half of cancer; the tumor was in her knee and the treatments didn’t do enough to eliminate it. Amputation was next. She worked really hard to get back on her feet; pacing the floors of her small room when no one was watching. It was my mom’s birthday, and we were giving her gifts. It was Laura’s turn, and she got up from the couch, and walked the length of the living room and back. It was a moment. It was her gift.

This would get the hospital reported today, but there was one chemo stint where I was really struggling with having to go back and forth to the hospital and stay away from her. She needed a bit of home, too. The nursing staff let me stay the night in her room, complete with my order from the hospital cafeteria menu. We played games, watched movies, I almost broke the bed because I kept playing with the buttons to move up and down, and we just were. I do remember that she had some pain through the night, so neither of us slept much. But, I felt close to her and was grateful to the nurses for breaking the rules.

The summer before she passed, Camp Good Days and Special Times entered our lives. It would be the only summer she would attend. I remember hearing about Camp early in her diagnosis, but she was not ready to go to “cancer camp” and just wanted to feel better. One of my little sisters and I also attended that summer, we went for the week specific for siblings. It became a safe haven, a second family, and a saving grace for us for many years.

In one week, she had an immense impact on Camp. She was the girl with one leg who tackled the ropes course. They fell in love with her, and she fell in love with them. So much so, that when we arrived the next week, the entire staff was waiting for us with open arms. We were Laura’s sisters, and they treated us like royalty.

That same summer, she was granted a wish from the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Her wish was for our family to go on a cruise. It was awesome. She was able to bring her best friend, and I got to stay in their cabin (how annoying!) They let me hang with them throughout, we saw so many beautiful islands, shopped, ate, played games and swam on the boat…it was a week of bliss and no thoughts of cancer. Perhaps the best, and most ironic, part was that the rest of us suffered from horrible seasickness. She felt great the entire time.

That fall, in the days leading up to Thanksgiving, we lost her. She was just 15, and I was 12, just a couple weeks shy of my 13th birthday. My younger sisters were 10 and 8. She was gone, our world was shattered, never to be the same again.

Her funeral was attended by many Camp Good Days friends. Some even served as her pallbearers. That Christmas, some of the Camp staff showed up with carloads of gifts. They called, checked in, served as a new support system — only having known her for less than a year.

We continued to go to summer camp for the years that followed. I started to volunteer and then worked there as a summer staff one summer in high school. I ran the camp newsletter, a responsibility I took very seriously. The year I graduated from St. Bonaventure, the Syracuse office needed someone to lead, and I called Gary Mervis, the founder of Camp, to learn more. He gave me a chance, and I took that job for a year. It was a learning experience (what did I know about running a board meeting at 22 years old?!?!?), but it gave me a good foundation.

Today, I am proud to say that I am a member of the Board of Directors and there is a road on the campgrounds named Laura’s Way. Camp will be in my DNA for the rest of time.

Fast-forward to my actual adulthood and I found myself starting a new job at a place that instantly brought me closer to my big sister. The first time I ever set foot on the St. John Fisher University campus, it was with my family at the Teddi Dance for Love in 1992. The Teddi Dance, a 24-hour dance marathon to benefit Camp Good Days, is a longtime tradition at Fisher. We were with Camp Good Days volunteers and campers, and the dance was named in her memory that year. I remember a loud and dark gym, but with lots of blinking lights and tired, sweaty college students. In those days, the participants had to keep their feet moving for all 24 hours. There were bathroom escorts to make sure of it! Students were spraining ankles, injuring their knees, there were EMTs stationed around the event. I remember having two distinct thoughts: “What kind of a place/dance is this?” and “This is epic!” I would have never guessed that 18 years later, I’d end up back at that place for a job interview and would land the gig.

When I talk to the students involved, I always say that my return to Fisher, in my mind, was serendipitous and fate-filled. It was a happy circumstance that brought me back — an opportunity I had been seeking and one that was closer to my family. But I know Laura led me here. I sometimes envision her hitting send on the email that included this job opening. I have made a career there, our family has found a forever home here, our girls have had a magnificent neighborhood and school experience, and I know — in many ways — I’ve got her to thank.

My relationship with my religion has ebbed and flowed since her passing. At 12 years old, I too, went to church because it was a part of a family activity, not by choice. The priest from our parish was a wonderful support to my family throughout Laura’s illness, though I remember once he came for a visit and she pretended to sleep and my mom was mortified (she was over the prayers at points). We took a break from church as a family for a while. I received my confirmation, but that was more of an event than a sustained weekly ritual. Again, time is blurry for me, but there came a point sometime after I got my license that I started taking myself to church. It became a solo mission to add back to my routine, be alone with my thoughts, and process prayer. We did ultimately start to go back to church as a family, but again, it started to feel like a family activity though our family had changed.

I remember in those first years of loss, too, always feeling like people were staring at us. The poor Lewis family. We were missing one of the “Lewis girls.” I ended up going to a Catholic college (Go Bonas!) and that time strengthened my relationship with religion. There, I attended weekly Mass on Sunday nights with my friends, so it was nice to have a new tribe for this.

I think of her daily. On her anniversary and birthday, and just about every milestone in my own life, I get into my own thoughts and wonder about her in that moment, time, and space. What would she look like? How would she sound? Where would she live? Would she be proud?

The toughest days for me were my high school and college graduations, my wedding day, the days my girls were born, and my 40th birthday. All to be expected. Her absence was loud and felt, yet, I knew she was close.

Today, she’d be inching closer to 50. I think she’d be living some distance from home, but would visit regularly. She’d be married, and wildly successful. I envision her in some sort of corporate job or leading a non-profit doing some worldly work. Her cancer would have likely taken away her ability to have kids, but I think she would have adopted. She always liked kids. She would be an amazing aunt and would be my confidante. I have missed her advice over the last three decades, and sometimes get really angry that she was taken from me. I get mad at the obvious (God) but then I get resentful toward my family, in some ways. My other half — the only one I knew at that age — was taken from me, never to return. I will grapple with that for a lifetime while also feeling lucky to have known an “other half” in the way I did at such a young age.

Of course, we remember her fondly and everyday, really. There are signs. Almost daily. At least one of us (my parents or sisters) notice the numbers 11 and 22 together - she passed on November 22. Whether it’s the exact time of day we look at a clock, numbers on a register, the list goes on. In the warmer months, any time a white butterfly passes us, we know it’s her. Because white butterflies pass us during all of the significant or meaningful moments, including when my husband proposed to me on my parents boat with both of our parents aboard. Songs, smells, cows (she loved cows); they remind us of her every day. I do think we work hard to keep her alive in so many ways, but it’s clear she is also doing that work.

Kate Lewis Torok is the director of marketing and communications at St. John Fisher University in Rochester. She, her husband, and two children live in Penfield, N.Y.

Final Thoughts on Finality

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

— For the Anniversary of My Death, W.S. Merwin (h/t

)Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning. Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop us a line if you have interested in either space at jaredpaventi at gmail dot com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook and LinkedIn. I’m also on Bluesky, and doom scroll Instagram at @jaredpaventi.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. For additional mental health resources, visit our list.

This, and the other blocked quotes, are from the feature written by M.C. Burns that appeared on the front page of The Herald-Journal in Syracuse, N.Y. on Nov. 25, 1991.

It has since been merged with another parish.

So damn powerful. Honored to have read this.