Checking your baggage at the door is an aspiration. Managers would love nothing more than for their employees to keep their personal stuff in the parking lot when coming to work, and I think the lion’s share of employees would prefer to as well. One of the ways you can achieve your work goals — however success is defined — is to bring your whole self to a project or task.

Covid threw a lot of these norms to the side as the non-essential among us shifted from desk-based to home-based work environments. My youngest, who was 2 1/2 then, periodically joined me for meetings. She didn’t understand that daddy was working; she just saw me in front of some screens and she was curious. Suddenly, the needs of our families were rocketed into the ring to fight for attention during the day with work matters.

Most people, myself included, coped while continuing to perform. Others struggled. Corporations and employers were tolerant, until they weren’t. The volume of articles on the topic split between business concerns (Rebuilding our culture! Cybersecurity!) and employee skepticism (They want to control us! They have too much real estate sitting vacant! They’re calling us back to blame us for a lack of performance!).

Checking all of your baggage at the door is as aspirational as it is impossible because employees are not AI-programmed robots (yet). Show me a person who isolates their work life from their personal life and I’ll show you a person with no life beyond work.1

As a human being, though, you are the sum of all your variables. I am a white male who is a spouse, and a father, and a homeowner, and a vehicle owner, and a son of an aging parent, and the caregiver for an aging aunt, and a sibling, and a friend. Whether I’m in my assigned cubicle or home office, I still have to balance the needs of parenting with work when it comes to doctor’s appointments or snow days or early dismissals.

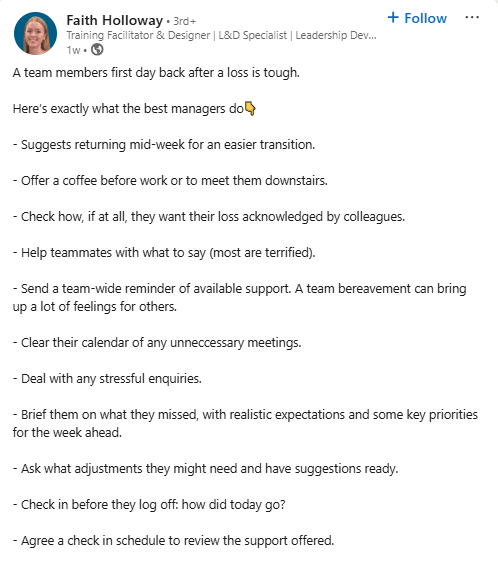

One of the traits you carry into work with you, like it or not, is grief. It’s something I had not thought about until one of my colleagues shared this LinkedIn post with me:

My grandmother died in 1999, within the first six months of my graduate assistantship in a medium-sized university athletic department. I was afraid to take time to attend the calling hours, funeral and associated family stuff.2 My supervisor was gracious with time. I took three days.

Working at a locally-based nonprofit afforded me quite a bit of runway with regard to emotional understanding. My boss was very accommodating with time off when my paternal grandmother and, later, grandfather died. She even came to the calling hours. I didn’t return to work with any sort of grief in any of those cases, having reached acceptance pretty quickly.

My wife’s father died in June 2023, following the last day of classes but before her state-mandated final exam. She was in and out of school during this period while her colleagues picked up the slack. She returned to work on the final day of her contractual year and worked an extra day to tend to everything that had been neglected.

Like most workplaces, schools vary in how responsive they are to the needs of their faculty and staff. My wife’s did what they needed to; they were understanding, gave her ample leeway in the days she worked, and ensured that everything else was covered. Now, it helps that she’s been a teacher in that building for more than 20 years, is established, and it was a time of year when there were no classes. She returned to work for a couple of days, still grieving her father but without the commotion of the regular school year when that might be noticed or recognized.

She has a much younger co-worker who experienced a similar situation this year. Her father unexpectedly was rushed to the hospital, where he spent his last couple of months before dying. The school was, again, supportive to the bare minimum degree. There was no plan for continuity in the classroom beyond whatever substitute could be found. Her colleagues, including my wife, pitched in to keep things afloat. Weeks later, she’s back to work as if nothing happen. She is, no doubt, still grieving just as my wife did. As we all would.

When it comes to loss, most companies have policies governing bereavement leave, but there is no handbook for how to manage a grieving employee. At best, you get the Golden Rule — do unto others as you would have done to you — and human kindness.

At worst? You get nothing from your employer.3

And that’s what Harvard Business Review found as a standard practice. In a 2019 article called When a Colleague is Grieving, the author Sally Maitlis wrote that employers are more willing to celebrate life events like the birth of your child than deal with the death of your loved one. “The default approach is to try to spare the office from grief, leaving bereaved employees alone for a few days and then hoping they’ll return expediently to work.”

Maitlis posits that work has become our second site but employers don’t act like it. Home is our first site, our safe space and locus of our university. The idea of a second site — the place where we seek fulfillment of social needs — used to interchange easily between our workplace, church, extended family, our local bar, or other recreational activity, but the dominance of work has pushed everything else to a third rung.

The workplace is a social hub for many. Think about a typical weekday: you get up at 6 a.m., report to work at 8 a.m., leave work at 5 p.m., and go to bed at 10 p.m. You spend nearly twice as long at work than you do at home. So, why doesn’t is our workplace more responsive? Your social needs don’t fulfill the bottom line. It’s said that a happy worker is a more productive worker, but somewhere there is an accountant4 balancing the opportunity cost of making you happy against the actual productivity gained. And, the return on investment isn’t convincing for them.

And that’s where the human factor plays in, because the cost is minimal. Maitlis spoke to a psychotherapist named Julia Samuel for this article, who said there are two instinctive responses to death — grieve and be sad, and survive and get on with it. Her belief is that when a manager gives their employee more than the bare minimum at their worst moment, this relationship will become an important support during the employee’s recovery. Samuel said, “The loyalty they’ll get, and the level of work, will far outweigh the input.”

So makes for a grief-friendly workplace? If you’ve read this far, you can guess: it starts at the top. Be present and available when learning of the news. Managers can begin by acknowledging the loss without making demands. Don’t ask how much time they plan to take or when they will be back. Offer condolences privately and don’t make a spectacle of it. And, be available. It may not be immediate, but your employee will have questions: what’s the bereavement leave policy, what schedule flexibility exists, what pool of paid time off can they use, among others.

When the person is away, figure out how to support them in their absence. At the very least, provide the continuity of their work so you don’t seem to blame a loss of productivity on their bereavement; instead of “Jared won’t get that to you until next week because his whatever died,” change the words around — “Jared’s whatever died and he’s taking time off. He’ll get the project to you after he returns.”

Supporting them also means reaching out. Being a manager doesn’t mean that you are a heartless bastard5 so send a card or go to the calling hours or dip into the petty cash and send flowers. As a manager, you represent the brand — you know, the brand…the thing whose value we discuss during hours of meetings each year — and your job in this instance is make sure your shattered employee in mourning understands that your brand cares about them. You can keep the boundary between personal and professional while standing in line at the calling hours.

Equally as important is the aftermath. Think of grief like a hip replacement. Just because you had the surgery doesn’t mean you aren’t going to walk with a cane for a while. You don’t come back to work from bereavement leave completely healed. In fact, you may have only started grieving by the time you boot up your work computer and sign in.

This is not to say that managers should treat you any differently, but they should have some different expectations. After my mother died, I took two weeks off during the middle of the semester and stayed home. When I returned, I checked in at my internship. My boss — a smartass who swore like a sailor — welcomed me back and asked, “So are you staying or going back home? I just want to know when I can start treating you like shit again.” It was a moment of levity and a message that things would get back to normal on my terms.

Managers need to understand that they might have a completely functional professional person one moment and, the next, someone so paralyzed by their own grief they can’t respond to a simple yes/no email.

Offering flexibility is also a huge asset, particularly in the short term. There may be meetings with lawyers, financial planners, government offices and therapists in the immediate days and weeks. Again, showing some basic compassion pays dividends in the long run, especially when your employee thinks about leaving the company. Would my next job be as accommodating as this one? It’s a valid thought and one that will cross their mind as they weigh a move.6

Most of all, what we all need to understand is grief and loss is going to become more common in our workplaces. The Baby Boomer generation is about 77 million people strong and well into retirement. Before that is the Silent Generation, or those born between 1928 and 1945. That’s a lot of older people — parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles — who will begin dying over the next 10-20 years.

Grief is going nowhere. It might even be moving into the cubicle next to yours.

Final Thoughts on Finality…

“Now majority rule is a precious, sacred thing worth dying for. But like other precious, sacred things…it's not only worth dying for; it can make you wish you were dead. Imagine if all life were determined by majority rule. Every meal would be a pizza.”

— P.J. O’Rourke7

Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning. Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop us a line if you have interested in either space at jaredpaventi at gmail dot com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook and LinkedIn. I’m also on Bluesky, and doom scroll Instagram at @jaredpaventi.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. For additional mental health resources, visit our list.

The other side of the coin is the person who spends all of their work time on personal matters and ignores their work responsibilities. I have worked with these people. They’re the people who don’t bother to do the bare minimum, but let their personal drama overwhelm themselves and everything around them.

Working in college sports then meant long hours, working weekends and a culture (there it is again) of being the first one in and the last one out. I don’t know how much has changed since then.

You might argue that an employer firing or berating you for your grief or loss would be worse. That’s fair. I’m always of the believe that no reaction is worse than any reaction. Indifference is its own penalty.

Actually, it’s probably a consultant making way more per hour on contract than you do in salary.

Though you it’s possible you are one. Try cosplaying as a human being.

It cross my mind before leaving my last job.

May he rest in power.

Jared — this article is one of the best I’ve ever read about grief. It’s real and honest, with very doable examples of things we can do for our colleagues or direct reports who are grieving. For a good year after my dad died, tears would randomly flow. Why? A memory flashed through my brain, a song stirred something in me, someone would talk about their dad…who knows what it would be. But I remember chiding myself and thinking, you can’t cry at work! Suck it up! I agree we should give each other permission to bring their whole selves to work. And if we can’t appeal to peoples’ empathy, then appeal to the bottom line. Workers that feel supported are more likely to stick around. I won’t bore you with more praise, but I will say that (with your permission), I will be sharing this article at my leadership trainings for new managers. Thanks for writing it!