Eco-Grief, Because The World's on Fire

Droughts, wildfires, intensifying weather, and the despair we feel for a planet we have harmed and are watching wither.

As a child of the 1980s, there are some bits of popular culture and history from the decade that are seared into my brain.

The Challenger explosion, first and foremost. You know, the time we all watched people die from the comfort of our classrooms and were sent home as if it was another day?12

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Hasselhoff, baby!

Michael Jackson. Thriller. We Are The World. The whole aura of him before his Dangerous album.

MTV and Live Aid. I lump these two together, unfairly, for convenience3.

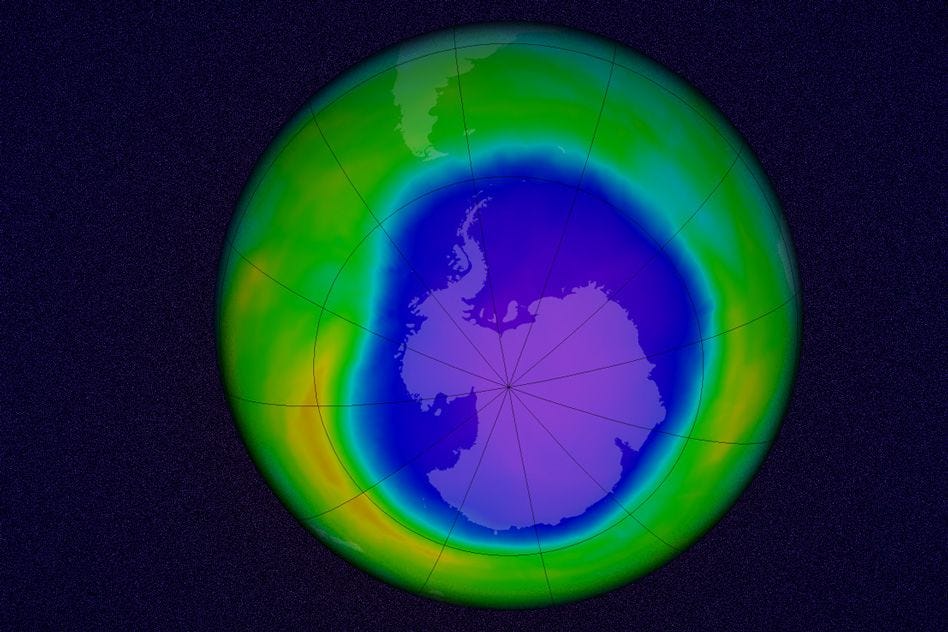

The hole in the ozone layer. <record screeches> Wai…what?

Yeah, the hole in the ozone layer.

Scientists discovered a thinning of Earth’s atmospheric ozone layer, a sort of sunscreen for the planet made of pure oxygen that filters out ultraviolet particles from the sun. It’s like SPF 30 for the planet, even though we still have to apply sunscreen to ourselves. Sunscreen is like renter’s insurance; your landlord has insurance for the building (ozone layer) but renter’s insurance covers damage to your personal stuff in the event of fire, theft, collapse or other disaster.

Anyhow, the ozone layer was thinning and there was massive global action due to the likely consequences — increased incidence of skin cancer and cataracts, plants and crops unlikely to adapt, ecosystems crushed by rising temperatures on land and at sea.

Scientists identified the cause quickly — chlorofluorocarbons, or carbon gases that deplete ozone in the atmosphere. It stands to reason when these gases are expelled and rise, they would counteract the oxygen barrier. But CFCs, as you might imagine, would need to be released in huge quantities to have this affect, right?

That’s where we come in. We being humans. Because, you see, CFCs are man-made chemicals. In the quest to find coolants for air conditioning and refrigerators or pressurize aerosol cans (like hair spray or deodorant4), we may have sacrificed some ozone in order to keep our milk cold and make mall hair a reality.

What followed was pretty amazing by today’s standards. Though scientists had been warning of this possibility since the mid-1970s, it wasn’t until 1985 when it really caught fire as a topic. The Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer called for governments to phase out CFCs, and laid the groundwork for, get this, scientists and policymakers to come together and create something called the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer in 1987. This was an historic treaty that held governments accountable to fixing the problem and, for the first time, recognized that climate, nature and pollution were all threats to the environment.5

The result? The hole should repair itself, in full, by the 2060s.

Identify the problem. Develop a solution. Implement the solution.

Seems simple enough. But, nothing is simple anymore. Take it from this dipshit, the late Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma6:

The era of global warming climate change pits science against policymaking7. The science is pretty clear; we’re feeling the affects of a changing climate created primarily by humans. We like our cars, but they run on fossil fuels. We like our food, clothing and other stuff to be dirt cheap, which places demands on shipping and freight systems (see also cars and transportation, which account for most of the carbon emissions domestically), requires industrial growth (see also increased emissions and pollution). We don’t like to change our habits based on the theoretical. We also don’t like it when some pencil-necked lab rats try to take away our freedom! Shit, we had a global pandemic and people were resistant to scientifically-proven practices that would keep them healthy. FREEDOM!

Digressing, human-driven climate change is a factor in our daily lives. Every summer seems to be the hottest on record lately. Syracuse’s famous winters have become extended autumns with snow. My hometown hasn’t broken the 100-inch barrier for snow accumulation in ages. What has changed is the intensity of the winter storms. Polar airstreams mix with warmer than normal fronts in the U.S. to create more powerful storms full of damaging winds.

What I’m saying is that affects of climate change are all around us. And some people aren’t handling it well.

Solastalgia

One of the first academic research papers adjacent to the topic of eco-grief is from 2004. A group of Australian scientists published a study8 of how environmental changes in New South Wales from mining caused distress among residents.

A new concept, “solastalgia,” is introduced to help explain the relationship between ecosystem health, human health, and powerlessness. We claim that solastalgia, as opposed to nostalgia, is a type of homesickness (distress) that one gets when one is still “at home.”

Though it has been studied for the past 20 years, the idea of grieving a planet that is changing for worse, not better, still a novel concept. But, by putting language behind it, the topic crystallizes for people who now feel as if they’ve been validated.

There have been images over the years that evoke a certain emotion with regard to sadness for the state of the planet. The Crying Indian9, polar bear floating on an ice cap, and collapsing glaciers have become emblematic of the crisis, but seeing a picture and feeling bad is not what we’re talking about here.

It’s how these pictures influence oneself and sparks feelings of grief, very much in the same way we grieve the loss of a loved one. It’s grieving what we’re losing, sort of like an anticipatory grief but with the anxiety that you’re going to feel the affects of others actions and inaction.

Point: Wildfires broke out in Ontario during late May and early June 2023, the result of drought from low snowpack and lightning strikes. They raged, sending smoke south into Upstate New York10. Schools canceled outdoor activities, sent students to remote learning, and/or closed windows to protect children11. Researchers found direct links between this event and increased anxiety, as well as some with PTSD. There was also a subset of people who drew connections to grief, as these events become more and more common. How can they go on with their daily activities if this is the way things are going to be going forward?

Dirt Nap Q&A: Dr. Heidi Scheiber-Pan

Dr. Heidi Scheiber-Pan is a licensed professional counselor and certified nature informed therapist based in the Greater Baltimore area. She founded and operated the Chesapeake Mental Health Collaborative, the first nature-informed group therapy practice in the U.S.

Scheiber-Pan specializes in the treatment of stress, anxiety and grief, and has begun treating people experiencing eco-despair and eco-grief.

How did you come to eco-grief as a topic?

My first client with severe eco-despair was a climate scientist, and I initially hesitated, feeling I might not be the right therapist because I also struggle with eco-anxiety; however, the scientist believed that made me the perfect therapist. We co-journeyed together, and since then, I’ve had more clients experiencing similar feelings.

As the conversation around climate change intensified, so did the need to recognize and name these emotions, and eco-grief became a natural extension of this dialogue. Over the years, I’ve witnessed the growing emotional and psychological toll that environmental degradation and climate change have had on individuals and communities.

We usually talk about grief in terms of people or pets and death, and sometimes abstractly like grieving a job or career. This is a very new concept that seems to have arisen as the conversation about climate change has intensified.

Eco-grief, while relatively new in the public discourse, is not a new phenomenon. Indigenous cultures, for example, have long held a deep awareness of the interconnectedness between humans and nature, and the grief that arises when that relationship is disrupted. As our climate crisis becomes more urgent, people are experiencing these losses more acutely, whether it’s the destruction of ecosystems, the extinction of species, or the erosion of places they’ve loved.

What makes eco-grief unique is that it’s anticipatory and ongoing — it’s a loss that we feel in real-time, even as we try to prevent it from worsening.

On the flip side of that coin, is eco-grief a self-inflicted pain because people are thinking too much about climate change?

I wouldn’t describe eco-grief as self-inflicted. It’s a natural response to the existential threat of climate change. To me, the real issue is that many of us feel overwhelmed by the scale of the crisis and powerless to make a difference. It’s not that we’re thinking too much about climate change, but rather that we don’t always know how to process the enormity of the problem. Eco-grief is not about obsessing over the issue — it’s about acknowledging the very real pain of living in a time of environmental crisis and finding ways to channel that grief into meaningful action and connection.

I find purpose in my work as a therapist and educator, knowing that by helping others process their eco-grief, we are building a collective resilience that is so necessary in these times.

You live in the Mid-Atlantic region, where severe weather is a threat year-round. Additionally, the Delaware-Maryland-Virginia area is noted for its oppressively hot and humid summers. How does the repetitive cycle of climate change impact a person mentally and emotionally?

The Mid-Atlantic region, like many others, has been seeing more frequent and severe weather events — flooding, heat waves, hurricanes — which undoubtedly takes a toll on mental health. People feel a sense of helplessness when these events happen, especially as they become more regular. It’s hard to ignore the anxiety that comes with uncertainty and the constant awareness that the climate is changing in ways that are beyond our control.

Mentally and emotionally, this can manifest as a chronic low-level stress, a form of hypervigilance. People may feel exhausted from the constant cycle of worry and fear, leading to eco-anxiety, depression, and sometimes feelings of paralysis or numbness.

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross famously outlined the five stages of grief — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. From your perspective, does eco-grief follow a similar cyclical pattern or are there other stages people face?

Eco-grief can certainly follow a similar pattern to Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief, but I believe it’s more complex and ongoing. There’s an added layer of responsibility and guilt that people often feel — wondering what they could or should have done differently, or what they can do now to mitigate the crisis.

Eco-grief can also involve periods of hope or optimism when positive changes occur, followed by deep frustration when progress stalls or regresses. It’s more cyclical than linear, with people revisiting emotions like anger, sadness, and acceptance multiple times, sometimes even in the same day. The stages of eco-grief are more fluid because the crisis is unfolding in real-time.

There are some recognized pathways to therapeutic treatment for people dealing with grief and bereavement of a death — talk therapy, social activity and engagement, etc. How do we treat eco-grief?

Eco-grief, like any grief, requires a thoughtful approach. I use the framework of Allow, Act, Adopt, and Attend:

Allow: Acknowledge and give space to your feelings of grief.

Act: Channel that grief into meaningful environmental action.

Adopt: Embrace healthy thinking and intentionally choose joy as a form of resistance.

Attend: Practice ongoing self-care and stay connected to nature and supportive communities.

Turning to the personal, when did you first encounter eco-grief?

My passion for the environment has been a lifelong journey. Even as a middle schooler living in Europe, I felt the urgency to protect nature. I organized a green team at my school to raise awareness about wastefulness and promote recycling. That was many years ago, and while the environmental movement has grown, it pains me now more than ever to see nature suffering even more under the impact of human activity. This deep connection to the natural world has driven my work today, particularly in addressing eco-grief and helping others process their emotional responses to environmental destruction.

How do you cope? What have you found works best for you in managing your eco-grief?

For me, managing eco-grief is a process of continual reconnection with nature. Spending time outdoors, whether through hiking, gardening, or simply sitting by a stream, helps me stay grounded and find moments of peace. I also practice mindfulness and gratitude—reminding myself of the beauty that still exists in the world and the small victories we achieve in conservation and restoration.

Finally, I find purpose in my work as a therapist and educator, knowing that by helping others process their eco-grief, we are building a collective resilience that is so necessary in these times. I often read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s quote to remind me of my commitment to joy.

Even a wounded world is feeding us.

Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy.

I choose joy over despair.

Not because I have my head in the sand, but because joy is what the earth gives me daily and I must return the gift.”

Final Thoughts on Finality

We are showered every day with gifts, but they are not meant for us to keep. Their life is in their movement, the inhale and the exhale of our shared breath. Our work and our joy is to pass along the gift and to trust that what we put out into the universe will always come back.

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning. Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop a line at jaredpaventi@substack.com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook, Twitter/X, and LinkedIn. I’m on Threads and Instagram at @jaredpaventi.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. For additional mental health resources, visit our list.

If you’re up for a truly frustrating read, I cannot recommend Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space by Adam Higganbotham enough.

And you wonder why Gen X is the way it is?

Take a couple of minutes and relive Queen at Live Aid, one of the greatest live sets ever staged.

Remember spray deodorant? Not the dry stuff my daughter likes, but the big steel cans of Sure or Arid that you would mace your armpits with every morning? Gee, that was fun.

Governments and scientists worked together. Novel.

I have no problem maligning Sen. Inhofe, who called the EPA a “gestapo,” openly hated LGBTQ+ individuals, blamed the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting on immigrants, advanced English as a national language xenophobia, and used federal funds to pay for his Christian mission trips to Africa. In summary, fuck him.

And, by virtue of things like the Citizens United case and the insinuation that money is speech, commerce is also fighting science.

Connor, L., Albrecht, G., Higginbotham, N. et al. Environmental Change and Human Health in Upper Hunter Communities of New South Wales, Australia. EcoHealth 1 (Suppl 2), SU47–SU58 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-004-0053-2

True story. The indigenous person in this ad is actually Sicilian. And, yes, I know I’m not supposed to say Indian. But, it’s so fitting that American ad agencies wouldn’t even cast an indigenous person to play a, wait for it, INDIGENOUS PERSON.

On June 6, I hosted a media event for my real job. TV stations attended, partially for my event, but so they could also get unobstructed views of the haze. It was eerie and striking to see. I was outside most of the day and by the time I got home, my clothes smelled as if I was at a daylong campfire.

Never mind that this situation was exacerbated by the wealth gap. I, an upper middle class white, shut my windows and ran the A/C. That wasn’t the case for everyone, especially not people living in poverty or from lower socioeconomic classes.

Thank you. I remember that 6/6 event and only in hindsight did I realize it was from the Canadian fires. That noted, I'm constantly thinking about climate induced issues and am so frustrated at the lag time of efforts. Would love to learn more about international efforts and what we can do on a local level - not that you can do that in one Dirt Nap.

As I read this week’s article, I couldn’t help but think of the victims of Helene in the mountains of North Carolina. The world they thought they understood has been shaken to the core. They likely can’t put a name to it (eco-grief) but they are feeling it deeply. How is that reality addressed as the region tries to recover?