Ed. Note: The community of people experiencing grief is vast and wide. Maybe you’re grieving a sibling or a friend, or a parent or spouse. Maybe you’re grieving your past or a future that will never come to be. Your feelings are valid and grief is an important feeling to recognize.

If you’re interested in contributing a Griever’s Digest, email me at jaredpaventi at gmail.com (or reply to this email). This is a community space. We relate together. We heal together.

It’s hard, but I promise you won’t regret it.

Griever’s Digest: Laura Brown

Some people don’t know where to start when putting together their thoughts for this feature. I personalize the Griever’s Digest Q&A for them as best as I can to jog their brains and organize their thoughts. Sometimes though, people come in with a thought in mind. Laura Brown is a teacher in the same school district as my wife and she offers this essay on her father, who died in summer 2023.

I left the funeral home carrying a box with a folded American flag, a Kelly green urn, a necklace to put ashes in, and many prayer cards. I secured the urn in my sporty Honda Civic. I giggled at the absurdity as I buckled in my father's remains. Who was I protecting?

Myself, mostly. My older sister had given me only one job. If I fucked this up, she would explode, as she was on her last inch of patience. My sister had controlled every aspect of the previous four weeks. Why did I even care enough to offer my help? Why did I even want a job in the mess that was my father's life and death? Was I simply attempting to claim him for my small part in his life? Biologically, he was my father, but the title never fit the man. Did I know this urn any more than the man in the box beside it?

I had to stop at Wegmans on the way home from the funeral home. I hysterically laughed as I realized I was taking my father, or what remained of him, on his last trip to one of his favorite grocery stores. Through tears, I said, “Okay, Dad, we are going to Wegmans.” My grief ears heard his loud, rumbling laugh from the passenger side. We shared one final joke about his penchant for the Wegmans shopping experience.

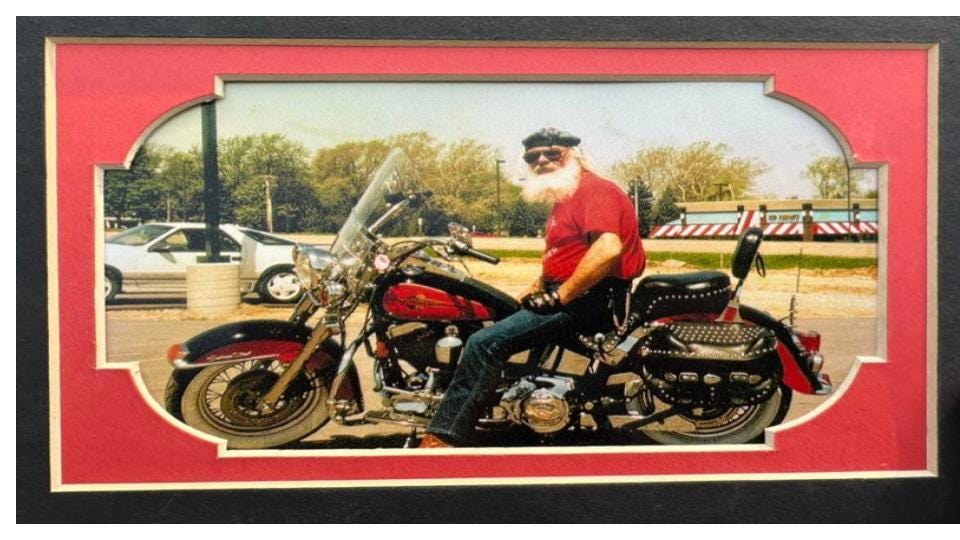

Typically, I had hoped to avoid a run-in with him when going to Wegmans for a weekly shopping trip. Sometimes, I would hear his deep voice before I saw him. In that case, I would maneuver to another aisle and stay alert. Other times, I would spot his tall frame and brilliant white beard. (He once did a stint as a mall Santa.) In a few instances, I had false alarms when viewing what looked like his army green jacket down an aisle.

The worst encounters were when I had lulled myself into a sense of peace. I had not seen him for months, and then suddenly, he saw me first and would say: “Hello, Darling.” He had a rich voice and was accustomed to people believing his bullshit for a certain amount of time. He effused a certain charm that fostered his five marriages and countless girlfriends.

My father’s entrance into my consciousness proved I belonged in the family, even if my paternal jigsaw piece was often missing.

But on this day, four weeks after his drowning, I got to control the encounter. As I pulled into a parking spot, I contemplated bringing him into the store. I could give him one last time around. It was not a Harley ride, but it was food, his second love. He would always buy fresh bread and savor it. He would talk about how he loved Wegmans produce and how it was superior to most. He had traveled around the country and appreciated Wegmans’ standards and quality. Standards and integrity were inconsistent qualities and values for him. He was dichotomous with minimal positive qualities as a parent. That was him, a contradiction between standing up for workers’ rights and failing to protect his daughters during their childhood.

I “met” my father on many occasions. The first time, I was seven, and the last as I was 50, carrying his remains into a store he frequented. I felt a need to honor him in some way; a man who desired to be honorable. He wanted to be well thought of and some did think highly of him for a while. He talked a good game. He was often helpful. He was affectionate. He said, “I love you.” He would tell a good tale. His behavior was aspirational. He tried in spurts.

I remember meeting my father for the first time at the tender age of seven. Having left when I was one, the adults acted like it was no big deal that I was meeting my father for the first time in my memory. He had returned to Syracuse from Illinois with a third wife, two stepkids, and my adorable three-year-old half-brother. I distinctly recall getting out of the car to see him standing in my grandparents’ front yard with this brood of strangers. Fortunately, my grandparents had made sure to be in our lives. My father’s entrance into my consciousness proved I belonged in the family, even if my paternal jigsaw piece was often missing.

On the day of my first meeting, my father was wearing a light brown leather jacket and a cowboy hat. He appeared like a giant to me at 6 feet, 4 inches tall. As I clung to my sister, I felt super anxious. I do not recall my mother’s presence or discussing my thoughts and feelings with her. It felt like I was thrown into a den of strangers with the familiar characters’ backs turned. They wanted to let my father handle this situation. They had no words to help me.

That weekend, he served me runny, over-easy eggs. It could have been excrement on the plate; that is how I felt about eggs as a kid. I was in my no-egg era, but how would he know that? How could he have a clue about his middle kid? He claimed (later) that my mother would not let him see me, but I remember a man who resembled him coming to the garage door to pick up my sister. I sensed some importance to his visit, but I must have been 5 or 6. It wasn't until I saw a photograph of him that my sister posted on her dresser mirror that I began to catch on.

As I was learning to write my name with careful penmanship, I often noticed how my sister would write a different last name. I would view her anger and rebellion when my mother scolded her to write our current, correct name. She was 5 1/2 years older than me; she knew who she was. I was confidently writing a false name until I entered the second grade. Not that my sister had it better; on the contrary, her life was a nightmare that dear old dad did nothing to make better.

Two young grandchildren were there on the boat and in the water when their grandfather jumped into the lake and drowned. But the next day, they are at a mall trying to do something physical to help their mental loads. Grief is a funny, unpredictable catalyst for behavior.

We shared a massive room with a walk-in closet when I took that photo from her dresser mirror and poked holes with a sewing needle. I had no words for my realization that I was living a lie. At 6, I had the epiphany that my days of picking berries and roaming our country acres were a fantasy. The truth was that we were living with an abusive man who enjoyed controlling and beating weaker human beings. The truth was we had to leave the lie and move on.

But none of these thoughts are in my head as I push the cart (and my father) through Wegmans four weeks after his death. Instead, I am in this state of inappropriate death humor. I must have had an insane expression on my face. I felt crazy. I mean, I was pushing the ashes of my deadbeat dad in a grocery cart. I could have left him in the car, but that seemed not very daughterly of me. Everything sane was removed from my wheelhouse. I knew that I had to go through this in my dysfunctional way; you know, the family way.

Let's pretend that I am not having a bit of a breakdown that has lasted a month because we could not bury him quickly. An autopsy was slowly completed; the veterans cemetery had a limited service schedule, and his 13-year-old grandson, who witnessed his death, needed to travel from Illinois. The grief process was prolonged like a school day before a much-needed break.

I tried to be helpful the day after his drowning. I brought food. I cleaned up my niece's home when she asked me to help. I was expecting something…something else. When I entered her driveway, she was still going to the mall with the two youngest members of our family. Two young grandchildren were there on the boat and in the water when their grandfather jumped into the lake and drowned. But the next day, they are at a mall trying to do something physical to help their mental loads. Grief is a funny, unpredictable catalyst for behavior.

As I waited in my niece's driveway, my former sister-in-law arrived after driving almost non-stop from Illinois to New York. Her son, already burdened with my half-brother's crimes, did not need this type of traumatic experience. It is no wonder she quickly scooped up her son and drove home. I selfishly wanted to gather with them, but did not blame her. I removed my children many times from the conflicts and this one was a doozy.

Broken families don't mourn together comfortably. The problems in our relationships had spotlights on them as I tried to console my niece, but she seemed in shock from trying to resuscitate her grandfather. As a medical professional, she must repeat that day in her mind. At first, my sister said she was not coming to her daughter's home as she was babysitting my father’s fiancé. But I sensed something was brewing underneath the surface. My cousin drove in from Ohio. We are supposed to gather. We are Irish-Catholic Americans, and gathering is a requirement. It is what we have done with other loved ones. We did it for Grandpa and Gram. We even gathered when the uncle left for life in “college,” a euphemism for a life sentence. I ran to Ohio for my uncle and aunt, their passing just 16 months before each other. Why can't we do this for my father? Is it because of our mixed feelings for him or our judgments about each other's differing feelings about him? Are we all so emotionally stunted that we can't connect? Is it because we are sober? For many reasons, we are not a cohesive group. My sister and my father's fiancé arrive by the night’s end. We look through photographs together, but everything feels awkward and unsaid.

Four weeks later I shop with a box of ashes, picking up carrots, celery and cucumbers. I decide on some cheese and crackers. I buy copious amounts of food to cope by keeping myself busy. My family members plan to come to my house the night before the funeral. The plan is to make photo collages. It is summer and we are living off savings. My husband has injured his hand and will be unemployed for many months. My estranged father is dead. My oldest begins college in a few weeks. We are living off fumes. My daughters and husband treat me like glass. It's fine. It's all fine. I continue to shop and push down my feelings. I have no feelings today that I can acknowledge. No, today I am taking my father to Wegmans. I am giving him one more ride.

I remember the one occasion he gave me a driving lesson. We were on a back country road in a big, old sedan that my maternal grandmother found, probably from one of her lady friends. It was too big for me; I don't recall having power steering as one of its features. I had to use a pillow to prop me up over the steering wheel. He told me to stop, and I didn't realize that a car was close behind. Luckily, there was no collision. During his drinking years, my father wrecked more vehicles than most own. He was sober by the time I was 16, but he only gave me one lesson. My memories of him are distinct because I saw him so infrequently. He focused on his new family; he moved back to Illinois by the time I was in college. He inquired about my fiancé’s last name the day before my wedding. I did not ask him to give me away. He was not there in the waiting room as my daughters were born.

Around 2009, I was giving my daughters a bath when he called to tell me he had kidney cancer. I gave him another chance. This time, he could meet his granddaughters. I was happy and thought that this would be different. After his recovery from surgery, he moved back to New York. I tried. I did. I went on a trip to D.C. with him. I witnessed his love for the New York State Fair. We went apple picking and sledding. But, he would show up unannounced at mealtime. He would act magnanimously and declare what a great guy he was. My stomach ached with each activity. I never felt calm in his presence. It was like he was playing a role. His acting could have been better. So, when his only son, my half-brother, committed some heinous crimes, I looked at my father with clearer eyes. He had raised his son poorly. I realized that I had no respect for my father. I didn't think he was a good person. I never gave him another chance to “meet” me. I am at peace with that decision.

The last time I saw my father was near the seafood section at the Wegmans where I was now carting him around. He was talking with a lady and seemed so earnest. I skirted right by him, not knowing that would be the last time I needed to avoid him.

How do you grieve a parent who wasn't very good at parenting? How do you honor half of who you are when you worry that you inherited the combined stupidity of both of your parents? I tell you what you do: you strap your father’s ashes into that grocery buggy, and you have one last experience with a man you called “Dad.”

Laura Brown is a social studies teacher at Liverpool High School, a mother of two children and occasional writer for The Educator’s Room. This entry was edited lightly for style.

Final thoughts on finality

“Death and life are not in opposition. So when someone tells you to live every day like it’s your last, kindly tell them to fuck off. They’re wrong. You should live every day like it’s your first. Live it like it’s your last and you’ll just run around like the house is on fire. I don’t want a bucket list. I don’t wanna live like I’m dying. I wanna live like I’m living. And I want there to be more possibilities left when I die, not NONE. Why rush to tick off all of those boxes? You don’t get a fucking gold star from God for that. I know now that I am going to spend the rest of my life incomplete. But life was designed to be incomplete. It’s not a worksheet you fill out. It’s an open platform. You do some things, but you also leave behind infinite possibilities for those in your wake. That’s the freedom.”

— Drew Magary, The Night The Lights Went Out: A Memoir of Life After Brain Damage

Dirt Nap is the Substack newsletter about death, grief and dying that is written and edited by Jared Paventi. It’s published every Friday morning. Dirt Nap is free and we simply ask that you subscribe and/or share with others.

We are always looking for contributors and story ideas. Drop us a line if you have interested in either space at jaredpaventi at gmail dot com.

I’m all over social media if you want to chat. Find me on Facebook, Twitter/X and Bluesky. I’m on Threads and Instagram at @jaredpaventi. You can try messaging me on LinkedIn, but I don’t check my messages regularly.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. For additional mental health resources, visit our list.